Thesis: Introduce flaws into LLM text.

I’ve been struggling a bit with articulating this one to myself, so I reached for a metaphor. I think what I want to say here is that, since the text produced by LLMs is so dull and lifeless, writers who use them may need to think about ways to introduce creative flaws to make the final product more humane.

A bit like kintsugi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold so that the cracks, ruptures, and gaps become part of the beauty of the design. I asked ChatGPT to explain how the philosophy of kintsugi applies to an individual’s personal growth, and here’s what it said:

When applied to personal growth, the philosophy of kintsugi suggests that our imperfections, mistakes, and challenges are not things to be ashamed of, but rather experiences that can make us stronger and more unique. Just as the repaired pottery is more beautiful for having been broken, individuals can become more resilient and authentic after overcoming adversity. This process involves embracing our struggles as part of our personal narrative, instead of trying to cover them up or pretend they don’t exist.

Right on.

So how can we train students to introduce creative, beautiful, productive flaws (“flaws”) into their writing? And what do I even mean by that?

Slang and non-Standard Written English is one way to find voice, and one that a chatbot struggles to do with anything approaching authenticity. ChatGPT writes in what I call Corporate American voice, unless you prompt it differently. But please don’t, unless you’re looking to cringe. Here’s ChatGPT again:

When it comes to leveling up in life, kintsugi vibes remind us that our flaws, fails, and tough times aren’t something to hide—they’re low-key what make us real and one-of-a-kind. Just like cracked pottery that’s glued back together is even more fire, we get stronger and more legit when we bounce back from struggles. The key is to own our mess as part of our story, instead of acting like it never happened or trying to fake perfection.

Prompt: “Rewrite that paragraph using Gen Z slang.”

To which I retort,

So one idea is to encourage students to inject standard academic discourse with an appropriate amount of slang or other varieties of non-standard Written English. This could be part of written assignments, no matter how formal. We can show them models of academic writing that incorporates AAVE, for instance, opening the doors to conversations about linguistic justice. (A topic that’s all the more today important given the well-documented bias in chatbots toward the variety of English preferred by corporate boardrooms.) For students, judging what counts as “appropriate” would become a learning opportunity and would lead to productive conversations about negotiating audience, genre, and context while maintaining one’s unique voice and perspective.

Another idea I have, one inspired by kintsugi, is the idea of the artful gap—or, to grasp at another metaphor, something akin to Miles Davis’ line that “music is the space between the notes.”

All of my favorite writers leave little, poetic, cognitive spaces between their ideas, almost like they are goading their readers to keep up with them.

Here’s Virginia Woolf, in the last paragraph of To The Lighthouse:

Quickly, as if she were recalled by something over there, she turned to her canvas. There it was—her picture. Yes, with all its greens and blues, its lines running up and across, its attempt at something. It would be hung in the attics, she thought; it would be destroyed. But what did that matter? she asked herself, taking up her brush again. She looked at the steps; they were empty; she looked at her canvas; it was blurred. With a sudden intensity, as if she saw it clear for a second, she drew a line there, in the centre. It was done; it was finished. Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.

A big part of what’s artful, I’d argue, in Woolf is her impressionistic style that blends an embodied, subjective narrative voice with external observations. She gives us just enough words to create the sense of being in someone else’s head while still being able to imagine the external world the character inhabits.

And here’s Tim Kreider, in “Lazy: A Manifesto,”1 writing about the modern plague of pointless business:

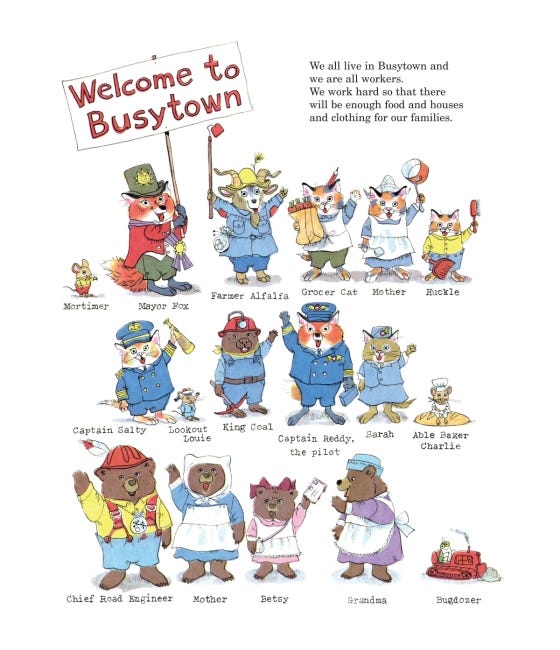

I can’t help but wonder whether all this histrionic exhaustion isn’t a way of covering up the fact that most of what we do doesn’t matter. I once dated a woman that interned at a magazine where she wasn’t allowed to take lunch hours out, lest she be urgently needed. This was an entertainment magazine whose raison d’etre had been obviated when Menu buttons appeared on remotes, so it’s hard to see this pretense of indispensability as anything other than a form of institutional self-delusion. Based on the volume of my email correspondence and the amount of Internet ephemera I am forwarded on a daily basis, I suspect that most people with office jobs are doing as little as I am. More and more people in this country no longer make or do anything tangible; if your job wasn’t performed by a cat or a boa constrictor or a worm in a Tyrollean hat in a Richard Scarry book I’m not convinced it’s necessary. Yes, I know we’re all very busy, but what, exactly, is getting done? Are all those people running late for meetings and yelling on their cell phones stopping the spread of malaria or developing feasible alternatives to fossil fuels or making anything beautiful?

Part of what’s delightful in here are the jumps between sentences. We’re not cluttered with clumsy transitional phrases like, “For example.” Instead, we get the treat of following Kreider as he jumps from observation to anecdote to wry commentary to a highbrow literary allusion.

I prompted ChatGPT to “write an engaging paragraph how people use business to mask the meaninglessness of their careers. Use specific examples form personal life.” It responded:

For many, staying busy can be a shield against the emptiness of a job that lacks deeper meaning. I’ve seen this firsthand with a close friend who, despite having a corporate job that left her unfulfilled, constantly filled her days with meetings, deadlines, and endless emails. She’d brag about her packed schedule and late nights at the office, using busyness as a badge of honor. Yet, beneath the surface, it was clear she was trying to escape the disconnection she felt from her work. Her calendar was a fortress, built not just to manage tasks, but to mask a growing sense of dissatisfaction. Instead of confronting the lack of passion in her career, she buried it under a mountain of activity, convincing herself and others that the whirlwind of her days meant success and purpose.

I was impressed by the “fortress” metaphor, and it’s interesting that the bot introduces a fictional female friend not unlike Kreider’s example (I did not feed his paragraph into the prompt). But the rest of it feels rather cliché—it doesn’t brim with life the way Kreider’s prose does.

Potential Teaching Applications

As an exercise, either have students generate a paragraph-length text with a bot or provide them with one, then ask them to

fuck it upintroduce interesting “flaws” to make it human, and humane. “Rewrite the bot’s paragraph introducing an appropriate amount of slang to convey your unique perspective while also maintaining a professional tone.” The more I interact with bots, the more invested I become in seeing a human fingerprint in writing.Take a bot-generated text and ask students to highlight the clichés. While the bot gives us “packed schedules and late nights in the office,” Kreider paints an image of a pretentious “entertainment magazine whose raison d’etre had been obviated when Menu buttons appeared on remotes.” This exercise would help them a) recognize the preponderance of clichés and empty platitudes that comprise most bot-written-text (bottext? bot-text?) and b) recognize when they themselves slip into relying on clichés.

Starting with a generic bottext, have students work in groups to replace those clichés and generalizations with a pithy, concrete image or example.

These ideas all stem from what will be the subject of another post, “Death of the Author/Birth of the Editor.”

For example…

I said to ChatGPT, “I've started a blog about LLMs and teaching called "Ship of Theses," which is a reference to the myth of the Ship of Theseus. How would you describe the blog's relationship to this myth?” It responded,

Your blog title "Ship of Theses" cleverly plays on the Ship of Theseus myth, highlighting the parallels between the myth and the evolving nature of teaching and learning in the context of LLMs. Just as the Ship of Theseus raises questions about identity and continuity, your blog explores how the integration of LLMs in education might alter traditional teaching methods and the role of educators. It suggests a space where old and new ideas about learning coexist, prompting reflection on whether the essence of education remains the same as these new technologies are adopted.

I then put on my editor’s hat and went to work in a Google Doc, giving some notes:

I then rewrote the paragraph with the goal of making it personal, conveying my voice, and introducing some “artful gaps.” Here’s what I came up with. It’s not much like GPT’s, but I did find it instructive to have a foil to write against:

The name “Ship of Theses” struck me one day while I was walking to class. As a dad, I’m contractually obliged to use dad jokes wherever possible, so it was the pun that initially won me over. I often tell my students that a thesis is “a claim to be tested,” both by the writer, while drafting, and the reader, while, well, reading. Framing my ideas about LLMs and teaching as “theses” to be tested out gave me a sense of freedom to try ideas about how the rise of chatbots would change composition pedagogy that had been percolating in the back of my head. I want to interrogate how LLMs will change how we teach and assess student writing, even as we hold on to the core of what we know creates the conditions for true long term learning.

Now that I’ve done this exercise, I’m tempted to assign something similar to my students. I wonder what they’ll do, especially to resist the anchoring effect of a bot’s first draft.

As close to a personal-philosophy-written-by-someone-else as I’ve ever found.